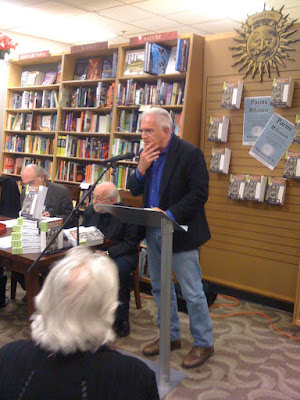

Michael Palmer reading Ernest Jones's "Songs of the Low" and other poems from the new Volume III of the Poems for the Millenium anthology, edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey C. Robinson, and devoted to "Romantic and Postromantic Poetry."

Michael Palmer reading Ernest Jones's "Songs of the Low" and other poems from the new Volume III of the Poems for the Millenium anthology, edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey C. Robinson, and devoted to "Romantic and Postromantic Poetry."

This trip was just about everything I'd hoped for: five days devoted to poetry in one of the most beautiful cities on earth. I did nothing whatever MLA related, though I did participate in the off-site reading at the Yerba Buena center on Sunday night (there's a story to be told about the poem I read but I'll save that for another post). But I went to all my favorite bookstores (the ones that still exist, that is; but I didn't make it to the East Bay to mourn for Cody's in any case) and bought a pile of things I have no time to read, and I hung out with my favorite people, and perhaps most significantly did a manuscript workshop on Saturday night with Richard Greenfield and Brian Teare and Catherine Meng (we also went over Cat's remarkable new manuscript, bits of which have appeared here and there, most recently in Fence: it's a book partly inspired by Lost and the questions of collective subjectivity and narrativity that that show's capable of raising in its finer moments). In the workshop, I was persuaded of a couple of things:

- The Odysseyan superstructure that I'd constructed this past summer as a means of freshening and re-opening the poems was actually a cumbersome distraction from the poems, which don't need its help.The problem of the new title really stumped me all day Sunday as I wandered about the city. I've used the old one for so long, and published many or even most of the poems with reference to it, including the chapbook-sized chunk that appeared in Conjunctions in 2004. The title has, at least in my own mind, taken on some of the attributes of a brand, which I'm leery of discarding. On the other hand, it's obvious that the poems need a new frame, a new handle, which will provide unobstructed (or unobstructive) access to them. At the same time, I need to honor the poems as they were written and the original impulses behind them, not thrash about in search of a "high concept" that will erase the slowness of their accumulation.

- The title, Severance Songs, has to go. Brian doesn't like "severance" because he doesn't think the poems are about that; Richard doesn't like the unreconstructed romanticism of "songs." Cat doesn't mind the title, but she does agree the book needs a new frame, and Homer isn't the guy to provide it.

- The individual poems may or may not need titles so their density doesn't overwhelm the reader, a real risk in a whole book of formally similar poems. (More formal variation or ventilation of some of the poems may also be required.)

Because they were written day by day, more or less in response to events in my life while living in Ithaca, I considered using a term like journal, diary, notebook, or daybook in the new title. But this would suggest a casualness that the poems, in their post-Stevensian density, simply don't reflect. Then I thought of using the word "sonnets," since the sonnet form is the most unifying principle of the book. None of the poems use end rhyme in any systematic way, but they're all about fourteen lines long and play with the argumentative structure of the sonnet; more significantly, the pursuit of an impossible ideal is the most consistent theme in the poems as a whole. But to use sonnets in the title would imply a sequentiality and completeness that's as false as the retrofitted Odysseyan superstructre. This is a serial poem, if it's anything, with the open-endedness and anti-narrativity that implies.

Browsing in Green Apple Books with Brian the next day, I mused to Brian that maybe I should simply name the book after the place in which I wrote it. Ithaca is out, obviously, and Ithaca, New York is specific in the wrong way. What about Southern Tier, I asked him. Then he reminded me that the Fingerlakes Region, and western New York in general, has another, more remarkable name that it acquired in the mid-nineteenth century: the burned-over district.

This immediately appealed to me. First of all, it plays with the idea of the poem as field or territory, and the ventilation of the poems is my attempt to deterritorialize the "little room" of the sonnet. Then of course there's the term's actual reference to the region I lived as a place so prone to spiritual uplift and transformation on a massive scale (in the Second Great Awakening) that it was spoken of as a place in which all the spiritual timber had already been used up. The Oneida colony, Joseph Smith and his golden tablets, the Shakers, and other such Transcendentalists avant la lettre all made their most significant spiritual discoveries in western New York. Finally, while on the one hand the term suggests devastation—a spiritual commons turned stale, flat and unprofitable from overuse—it also suggests renewal, as in slash-and-burn agriculture. All this seems to apply to what the poems actually are and do, in a way that the Odysseus model simply doesn't.

So, that's the new title of my revised manuscript: Burned-over District. I think that turns the corner and takes the poems into a new epoch, which is a movement I really need. Not just so that the book itself might see the light of day, but so I can begin to close the door on this project and start seeing what new things arise. I'm grateful, above all, for my poetry companions Richard, Brian, and Cat, part of my Montana cohort and, as I said that night, invaluable "continuity girls": the people who have known you and your work long enough to remind you of who and what you're really about. I've been struggling with my own love of beautiful language—a kind of Oedipal struggle with Stevens, who's the poet that first enabled my own writing at a tender age, and who's in my DNA now for better and for worse. My comrades gave me permission, and the book permission, simply to be myself. There's no greater gift.

No comments:

Post a Comment