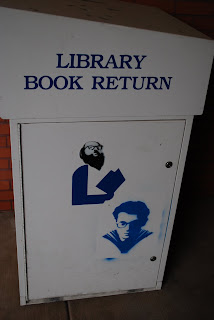

Outside the Allen Ginsberg Library at Naropa University.

For one solid week I took leave from my family and from my identity as poet to be a student in Laird Hunt's fiction workshop at Naropa University's Summer Writing Program. I arrived on Sunday afternoon filled with a mixture of excitement and nigh-existential nausea, such as I imagine afflicts secret agents. What would it be like to begin at the beginning--to sit at the seminar table and not be running the seminar--to be an unknown quantity in a tight-knit and storied community--to have so many poetry friends and acquaintances on the faculty while I went as a paying customer?

View of Naropa's front lawn, with a rather splendid tree.

Reader, it was glorious. Having checked my ego at the door, it was delightful to meet my fellow students around the ultramodern, coffin-like table in the shiny new Administration Building, and simply be one of them. I was happy to not be the oldest student in the class; there were quite a few twenty-year olds (a talented, ambitious, articulate lot, I hasten to add--like the best of my own students) but I was not the only one in his thirties and a couple of folks were in their forties. And looking around the room, especially once the class got going, I realized the benefits of taking a creative writing class as a full-fledged adult. I was not there to discover who I was, but what I was capable of doing. There was no vertigo, no posturing--I'm glad to say there was very little of this from my classmates, either. We got right down to business.

The workshop was excellent, not least for its being a workshop in a truer sense than usual: the emphasis was not on critique, but on producing new work. We read bits of the things we were writing, but the point was not to correct or polish this writing (or to grandstand opinions about it) but simply to hear it--to have a sense of the others were writing, and the immensely varied ways in which we were responding to the prompts and assignments. The title of the course was "Histories"; here's the description as it appears in the catalog:

Historical figures like Herodotus, Hannibal, Jesus of Nazareth, and Calamity Jane have all served as energy nodes around which writers have built significant works of prose. We’ll examine texts like Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter, Selah Saterstrom’s The Pink Institution, and W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn to explore that prose which, if we can kick awake that poor overworked pearl, posits the historical as its grain of sand. Students will produce their own writings for consideration and helpful critique.

I had had a sense, from his fiction and the little I knew of his biography, that Laird Hunt would be the ideal teacher for a poet trying his hand at fiction, and the gamble paid off. He spends a lot of time with poets--he's married to one--and has a deep appreciation for poetry, and seemed genuinely interested in what I was doing and the particular resources I as a poet might bring to writing a novel. My taste in fiction is very compatible with his: I revere Sebald and early Ondaatje, and though I hadn't before encountered the Saterstrom book I was drawn in by its unusual form, or forms.

"Histories" isn't for me the most compelling title for a fiction course; if I had any doubts about choosing it, it's because I don't think of myself as someone who is particularly interested in historical fiction. I would much rather engage with noir or SF. But the class reinvigorated the genre for me; it was approached in such a thoughtful way, and of course the model texts on offer were incredibly rich: in addition to the titles above we also looked at excerpts from Patrick Ourednik's Europeana, Toni Morrison's Beloved (such a strange book, such an unlikely candidate for mainstreaming, yet there it is, fully canonized), Lorine Niedecker's poem "Lake Superior," and one ringer: Tracy Chevalier's Girl with a Pearl Earring (a not-bad movie but from the looks of the prose utterly bogus and banal).

Jaime Enrique reads from his forthcoming novel about the life of Cervantes.

One of the most effective exercises Laird gave us was designed to confront us with what he called "the hobnailed boot problem"; that is, the often false-seeming or distracting images and details that writers of historical fiction toss into their writing to create that sense of the past. While we did some freewriting on a scene from the past, Laird intoned a few keywords that we had to wrestle with, though we weren't required to incorporate them into the text: "goblet," "Catherine of Aragon," all that great old Medieval Times-type malarkey. I much approved of his general technique as a teacher, which was to get us writing and then to throw a monkey-wrench into the process designed to momentarily estrange one from the task of assembling a mimesis and be confronted by what we were writing as language, material for working and reworking.

I am increasingly convinced that the most interesting fiction is not that which produces the most vivid representation of reality, but which puts mimesis in tension with words and the systems native to words (sentences, paragraphs). One of the books I devoured when not in class, though Laird didn't assign it, was Ronald Sukenick's Narralogues: a loose, sometimes irritating collection of stories with a provocative thesis: that fiction should not be considered as a mode of mimetic art at all, but rather as rhetoric. The goal of this rhetoric, furthermore, is truth: not Platonic truth (which representation will always fail to produce) but truth nevertheless (Sukenick deliberately allies himself with Plato's old enemies the Sophists). A novel is successful not because it represents reality accurately but because it persuades you, not necessarily to any action but of the truth-content of the novel's form. I find much to recommend this theory; not only does it provide a better or more interesting description of what some of the greatest fictions accomplish (Moby-Dick, Ulysses, Woolf and Kafka come to mind) but it brings fiction closer to poetry.

While all this was going on--and while I was discovering that my novel is in many senses historical, from its evocation of May '68 in Paris to its preoccupation with the theater of memory--a ferment of talks and readings, as well as a dozen other workshops were happening. Really, when I was researching the various summer writing workshops out there, there was nothing else to compare in terms of the diversity, rigor, and sheer creativity of the faculty: Charles Alexander, Junior Burke, Julie Carr, Linh Dinh, Steve Evans, Thalia Field, Ross Gay, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Laird Hunt, Stephen Graham Jones, Bhanu Kapil, Joanne Kyger, Jaime Manrique, Jennifer Moxley, Jennifer Scappettone, David Trinidad (and that's just for Week One!). Many of the people on this list are acquaintances and friends, and after some momentary hesitation on my part I was glad to find myself included in a number of intensive and convivial gatherings.

A purple pair: Jen Scappetone and the legendary Anne Waldman.

No comments:

Post a Comment